One of the most pressing themes from my childhood is the passage of time. It was a topic that was brought up frequently. An ever-present entity looming over us, showing up on holidays and special events to whisper in our ears that a whole year, or two, or three, or five had passed since the last time we celebrated a birthday or sat around the table at Christmas. I can still hear my parents, each in their own wistful sort of way, ask each other: “Can you believe it’s been [insert amount of time passed here] since…”

Memory is a fickle thing, but it seemed this meditation brought with it a palpable sense of grief —something lost, never to be held or experienced again.

My family certainly doesn’t have the market cornered when it comes to nostalgia; but perhaps its effect on me was the degree of nostalgia. Or maybe I was just more susceptible to the personal undercurrent it carried for them. Regardless, this sense of loss is something I internalized deeply.

I don’t know when I first became conscious of the way this became part of own emotional lexicon. I can’t remember when I first started saying, “Can you believe it’s been...” with my own sort of sorrowful longing, but I catch myself doing this all the time.

For almost as long as I can remember it’s felt like I’ve been in a fight against the inevitability of time. It’s always slunking around, like a house guest that just won’t leave. Leaning on all the furniture, throwing sideways glances and silently pointing at Its wristwatch. Tick, tock. I’m certain my gender and ambitions; my own predisposition to anxiety make all of this sharper.

Now that my daughter’s here I feel this even more acutely — I can see the time passing as she acquires new skills and grows out of the clothes that seemingly swam on her just the month before. These are certainly gifts, and yet I wake up some days and I feel panicked, like I want to grasp at something… but what? I’m not exactly sure.

What am I afraid of losing exactly? Am I afraid to forget? That I won’t remember exactly what her weight felt like when I held her at 6 months? Or when she ate her first strawberry? Do I feel like I have less and less time to realize my own dreams and goals? Or is it that I simply can’t come to terms with the idea that nothing is forever and one day everything I’ve ever known will be gone?

I can’t answer any of these questions for sure, but I do know I don’t want to live the rest of my life with this kind of relational angst.

Recently, I’ve been working on a kind of peace offering with Time. I would like to change the way I’m interpreting its story. Instead of focusing on loss, I want to better celebrate growth and change; and with it, the new experiences, insights and wisdoms.

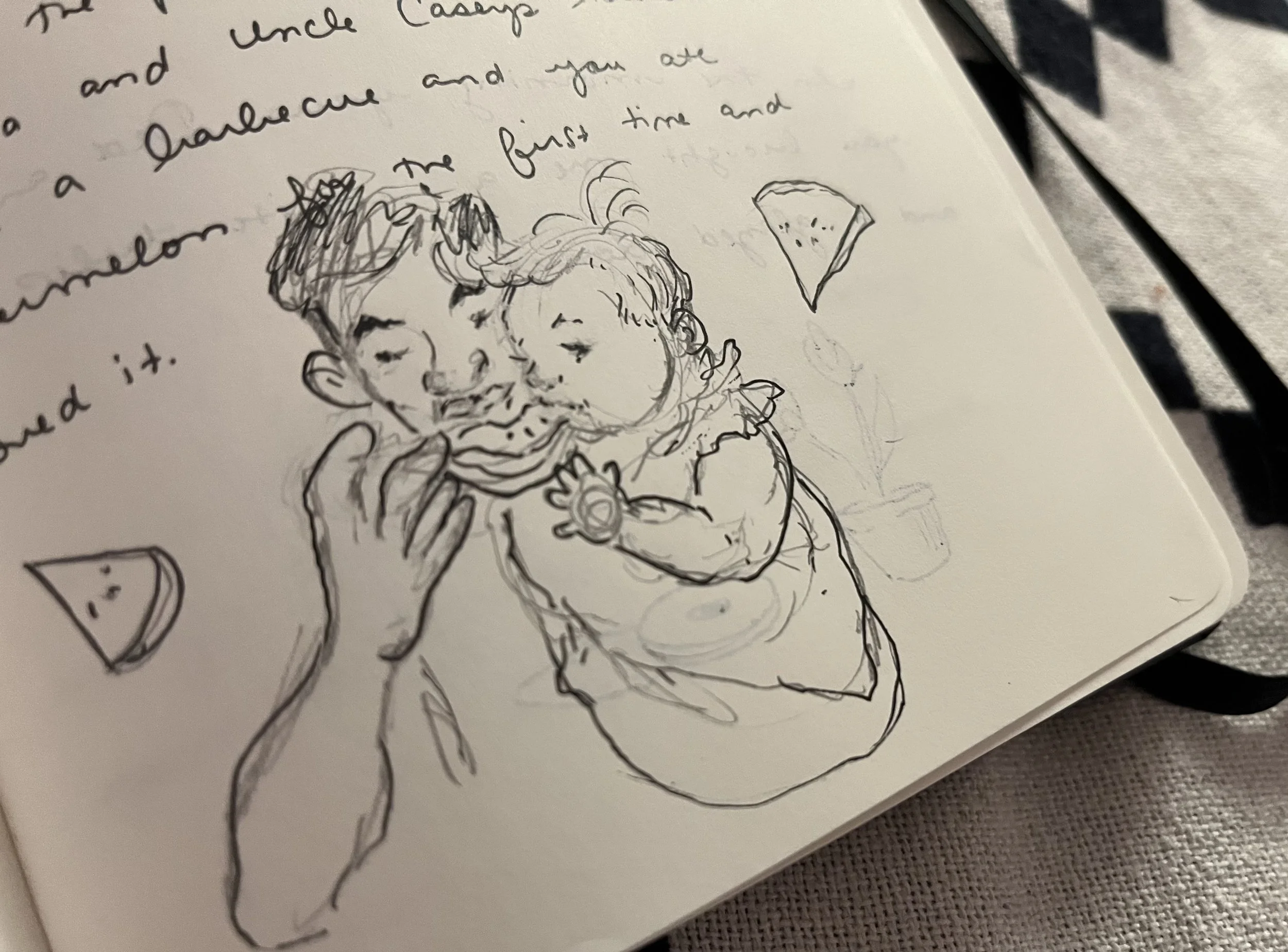

This is certainly shifting how I create and the marks I make. I find myself journaling more than ever before, and making more art, just for myself: a portrait that captures the gravity-defying nature of my daughter’s hair, a rough journal sketch of my husband feeding her watermelon for the first time.

I can’t stop time; but even if I could, I wouldn’t want that either. Not really.

The first time I heard the quote, “If you’re not growing, you’re dying,” it was part of a speech famed football coach Lou Holtz gave at an event I attended in my early twenties. At the time, this sentiment blew me away because I’d never thought about living like that before.

All these years later I’ve heard variations of this quote hundreds of times. Coach Holtz himself borrowed this quote from writer and artist, William S. Burroughs. The beauty of it is that it can be applied to so many aspects of ourselves. And yet, another perspective posits that from the moment we are born we begin to die — that the very quality of living is to walk hand-in-hand with death.

If I could stop time, any pleasure found in it would be temporary. Stagnation would set in, and along with it a multitude of little deaths: no more surprises to discover. I wouldn’t hear my daughter’s first words or improve my painting or ever finally learn how to play that one song on the ukulele. I know this, and yet the acceptance of the fact is still something of a process.

I suppose the trick of it all is to challenge ourselves to grow in all possible ways despite the inevitability of death.

And better yet, to celebrate the whole thing: all the beginnings and all the ends, knowing they are two sides of the same coin.